I arrived by bus in Labrang on a sunny but cool Saturday morning in May and the local Tibetans and Hui Muslims seemed to be getting along just fine. A bit of an improvement on Rock's time, when he arrived just after a bloody battle between the local Tibetan nomads and the Sining Muslims for control of the town. The Muslims had won:

"Frightful indeed was the aspect of Labrang after the fight. One hundred and fifty four Tibetan heads were strung about the walls of the Moslem garrison like a garland of flowers. Heads of young girls and children decorated posts in front of the barracks. The Moslem riders galloped about town, each with 10 or 15 human heads tied to his saddle..."

Rock explained that the Tibetans were fiercesome fighters but disorganised. They had charged the Moslems troops on horseback, impaling many of them with long lances "like men spearing frogs". But they were outnumbered and defeated by the Moslems, who were more disciplined and better trained. When they caught any Tibetans, they hung them up by their thumbs, disembowelled them alive "and their abdominal cavities were then filled with hot stones."

But in 2012, the former enemies seemed to have forgotten their differences. The Hui were indistinguishable from the Han Chinese, wearing modern clothes with just a skullcap or headscarf to show their faith. They were the proprietors of many of the beef noodle shops that lined the single street of modern day Xiahe. The Tibetans, however, were flamboyantly different. The young men swaggered along the main street, sporting chubas wrapped around their waists and shoulder length hair. Tibetan women wore long skirts and cowboy hats. Both males and females wore scarves around their mouths and noses, presumably to ward off the ever present dust, not to mention the chill wind. In some parts of town it was if you had stepped into a live fancy dress competition, with almost everyone living up to the cliched ethnic stereotypes for the cameras - Tibetan cowboys and kids with shiny red cheeks alongside austere Muslim old men in Mao suits and old fashioned ground glass round spectacles.

I had not been sure whether I would be able to visit Xiahe. As one of the largest Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in China, I had worried that it might be caught up in the recent waves of Tibetan protests and self immolations. But I was able to buy a ticket for the four hour bus ride from Lanzhou with no problems, and there didn't seem to be any obvious tension on the streets or signs of any additional police presence presence.

And so after checking in to the Baoma Hotel, I walked to the end of the road and entered the massive monastery complex to have a look around.When Rock got to take a closer look at Labrang during more settled times, he was awed by its size and the sheer number of monks in residence. He took photos in the 30 large buildings that served as chanting halls for the 5000 monks, and he marvelled at the huge kitchens with their five large iron kettles designed to make butter and and rice gruel to feed thousands at one sitting. He was less impressed by the dirtiness and squalid living conditions of the monastery and what he perceived as ignorance of the the Tibetan monks. He noted that the floors were caked in spilled rice gruel and butter tramped hard underfoot and now "many inches thick." And while the Abbott who welcomed him appeared wealthy, he was almost child-like in his ignorance of the outside world. The head lama told Rock how he knew there were people with the heads of dogs and cattle living in foreign countries "Our books tell of such people ..." He also told Rock that of course the world was flat, and the sun disappeared behind a big mountain that was situated at the centre of the earth.

In modern times, the Abbott no longer lived at Labrang, but was said to have an official residence in nearby Lanzhou, some four hours drive distant. And despite its size and hundreds of monks, the monastery seemed to be a little subdued. Perhaps it was because many of the "Tibetan' monks were not Tibetans, but ethnic Chinese. I overheard a few monks talking and had been surprised by their fluent colloquial mandarin. At first I presumed this was because they lived in close proximity to a modern city like Lanzhou. Then when I looked at them more closely, I realised they were Han Chinese.

As I toured the monastery complex I recognised a few of the larger buildings from Rock's pictures. Many of the smaller buildings were more recent additions or renovations, and the extensive living quarters for the monks now had satellite TV dishes ad a similar mirror-tiled satellite dish contraption that appeared to be used for making boiling water. And like the rest of China, much of Labrang appeared to be a work in progress, with older buildings being torn down and newer ones being built. The sound of modern Labrang was not the conch shell or trumpet, but the hammering of wood and iron, and the put put of the tractor carrying bricks and cement.

I was later to read that the Chinese government has just approved a massive new re-building program for Labrang, which would provide for renovation of many of the temples. This was, according to an Indian journalist writing in The Hindu, part of the PRC government's carrot and stick approach to preserving harmony and stability on the Qing-Zang (Qinghai-Tibet) plateau and winning the hearts and minds of the Tibetan Buddhists. It wasn't entirely successful. In a local cafe, I was accosted by a very laid back monk 'with attitude' who spoke halting English. He had learned the language, he told me, during the couple of years he had spent in India, where he had gone to study Tibetan Buddhism and pay a visit to the Dalai Lama in Dharamsala. I hadn't wanted to broach the subject of Tibetan politics with the locals I met on this trip, and I kept my answers neutral and to the minimum as the young Tibetan posed question after question about how Australia was independent and how he knew many Tibetan exiles who had moved on to places in Canada, Switzerland and Australia.

I took a clockwise walk around the circular kora circuit of the monastery, walking alongside many Tibetan pilgrims. Some were obviously just there for the day - mums and dads with their kids who had come by car or motorbike. But others were more devout - old grannies who shuffled along and young hardcore pilgrims who were prostrating themselves on the ground every two or three steps, which would seem to take them more than a day to complete the 3km circuit. The path climbed into the hills to the north of the monastery and I got spectacular views over the whole complex - and of the more mundane concrete sprawl of Xiahe beyond. Across the valley and over the Sang Chu river there was the hillside covered with trees - " a forest of fir and spruce. It is of miraculous origin, say tradition. Long ago a famous monk, the founder of Labrang, got a haircut. His hair, scattered over the hillside, took root and produced this fine forest," according to Rock. This appeared to be the vantage point from where Rock had taken his panoramic photographs of the monastery, but I found it was now difficult to get there.

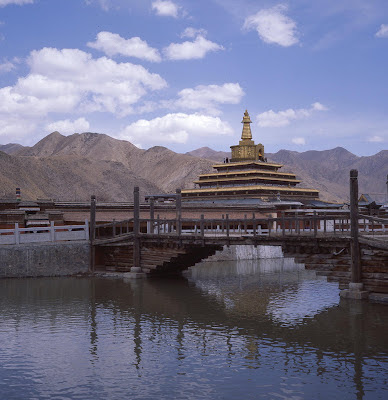

The next day, after the usual fitful high altitude sleep, constantly waking up with a dry mouth (Labrang is 8,600 feet above sea level) I tramped out in the early morning to try ascend the hillside. However,a the new road running through the valley had been carved out of the hillside, which left a steep cutting that was impossible to climb up. There was a new condominium block that was being constructed on the hillside with no doubt idyllic views over the monastery, but I was waved away by the construction workers. So I ended up at the big square thanka display area further down the road, the tourist viewing point overlooking the big golden pagoda. While most people took in the view and turned back here, I carried on up a dirt track to try climb the much higher ridge to the south of the monastery. At first, it was a pleasant stroll through rolling grassland. I was soon all alone and I spotted a couple of marmots, whistling and rushing to their burrows. Rock had seen marmots during his trek over the grasslands and recounted how his dog ran itself ragged chased them, sometimes catching them, and sometimes getting a nasty nip from their sharp teeth.

As I ascended the grassy ridge the incline got steeper and steeper, but I seemed to be no nearer getting an unobstructed view of the monastery. It was only when I reached the summit ridge that I realised why nobody came up here - the view was blocked by the trees of the sacred forest! What a waste of a morning! And then I also had to face a much more scary descent down a steep gradient, which hadn't seemed half as steep on the way up. I was glad to get down in one piece.

I spent another lazy afternoon in sunny Xiahe, idling in the Nomad Cafe and watching the street life. Tibetans seemed to like to sit in cafes too - sipping butter tea and chatting away. I chatted to the owner of the Overseas Tibetan Hotel and asked about how to get to Choni. No direct buses, she told me - but get an early bus to Hezuo (Gannan) and you can get a Choni bus from there, she said. And so on to the next part of my quest. PS: I didn't do any direct "then and now" comparison pictures at Labrang. However, the building (and tree) in the background of the photo below taken by Rock in 1925 appears to be still standing, as seen in the picture at the bottom.

No comments:

Post a Comment