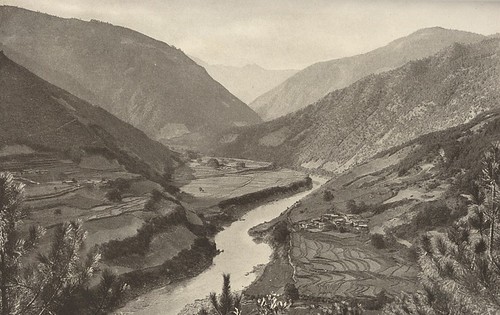

The Mekong in 2001 and 1924: the top picture shows the river during my recent visit, the lower picture shows a similar scene captured by Joseph Rock along the Mekong in 1924: the village of Londu.

When Joseph Rock set off from Lijiang, his main aim was to walk up the Mekong (Lancang Jiang) river towards the French missionary post at Cizhong (then known as Tsechung). Therefore, he had to first work his way around the Yangtze, which envelopes Lijiang in its first bend. He did this by passing through the village of Shigu, situated at the tip of the first bend of the Yangtze. If you want to read more about this town and its history, I suggest you read Simon Winchester's book Yangtze, which tell you more than you need to know about why the river makes such a weird deviation at this point rather than continuing to flow south. Shigu was later a historic stopping off point for Mao's Long March.

But back to Joseph Rock - he describes his journey with the usual woes about flea-ridden rooms and ne'er do well opium smoking Chinese. These grumbles are offset by his effusive words about the magnificent countryside he is passing though. I love his description of the scene from his balcony in the market town of Shigu, as his caravan seeks to settle in for the night. He describes it so well, you can imagine yourself right there. He is watching the scene as it rains and while "cats dogs and dirty children add to the confusion":

"The lead mule with his large bell steps into the muddy courtyard, followed by his hungry co-sufferers. Without waiting to have their loads removed they fight their way to the troughs and try to eat through the baskets tied over their mouths. Dogs are stepped upon, pigs squeal, mules bray, while long dead ancestors are conjured up unprintable language by the exasperated muleteers. Everywhere mud, dung, cornstalks and odours which it would be difficult to analyse! Poor cook! In such surroundings he has to produce a palatable meal!"

On his way to cross the Yangtze-Mekong watershed, Rock passes the scene of a Nashi funeral, where grey cloaked mourners prepared paper replicas of servants and furniture to be burned to accompany the deceased into the next world.

He then passed along a narrow track where spiders webs were so thick as to need a stick to be held up in front of your face. In this way he plodded in five days up to Chutien, on the banks of a tributary of the Yangtze. This is the same route now followed by the bus that travels from Lijiang to Weixi, on which I travelled in 2001.

At Chutien Rock encountered the first signs of Tibetan culture, with a Buddhist temple in the town - the first or last outpost of Lamaism. He stayed in a loft from which opium smokers had been evicted and he marvelled at the clear country air at 9,000 feet, the stars overhead (there were holes in the ceiling) and the strange bunches of beans and white blocks of yeast stored in the room.

From here Rock crossed over to the Mekong via an pass called Litiping, which he described as undulating alpine meadows with hemlock, canebrake and rhododendrons growing in profusion, and birds singing. I must say that when I passed over the same spot I found it to be not quite so enchanting - a barren stunted grassland interspersed with sheep herders rock shelters.

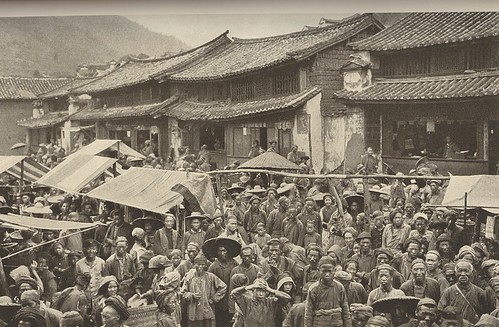

From this high point, Joseph Rock descended to Weixi, a small but substantial town where he paused to rest and restock his supplies, as well as develop some pictures. He said the town boasted a wall of mud, with a few dilapidated gates, and a post office where he was able - despite a lack of sufficient stamps - to post a letter to Washington DC. In Weixi Rock also spent a considerable amount of time providing medical care to the locals. However, he was dismissive of their blind faith in western medicine, and their expectation that just one dose of his pills would cure even end-stage tuberculosis. He also notes that the local cure for bleeding is cow dung.

My own experience of Weixi was of a very pleasant and rustic market town in the hills. It had some of the atmosphere of the old Lijiang, without the throngs of tourists. Its hilly streets were given over to stalls selling all kinds of wares, especially herbal remedies. I remember a few Burmese traders selling oddments like Vietnamese toothpaste and some Indian produced joss sticks. It reminded me that the Burmese border was not so far away. The other main thing on display in Weixi was orchids, literally hundreds of them. In late spring when we visited, there were scores of people trading plant pots containing these strange flower plants. Apparently the more aesthetic samples were changing hands for hundreds of dollars in the belief that they confer good luck

The main thing about modern Weixi is that it's character is predominantly Lisu. These people seemed to be a cheerful, industrious bunch, and in the higher reaches of the Mekong valley we found that many were Christian. Quite a few of the local villages had small churches, looking for al purposes like any other traditional Chinese building with the curved roof, but with a cross prominently displayed on the front. Funnily, Rock did not seem to remark on this during his visit - perhaps at that time the work of the missionaries in the Mekong had yet to bear fruit. The great British proselytiser, J.O. Fraser, was responsible for converting many of the Lisu to Christianity in the early 20th century, but his work only started around the Great War of 1914-18 and may not have had much impact on the Weixi area then.

Weixi is situated some way above the Mekong, and from here Rock descended to the village of Kakatang, where goitre was a major problem. One local man had such a large goitre that it weighed down his chin to the extent that he could not close his mouth. Needless to say we saw no such evidence of iodine deficiency on our 21st century visit.

Rock continued on to the village of Petsinhsun - now know as Beixincun - where the headman wanted to have his photograph taken. Rock was amused to see him throwing on silk garments over his dirty clothes and then posing as if he was the emperor of China.

As he progressed further up the river valley, Rock noted there were less Lisu and Naxi people and more Tibetans in evidence. And the Naxi who did live in the Mekong valley had adopted Tibetan ways and followed a Tibetan form of Buddhism. Up through Kangpu to Yetche, he met a Naxi "king" who he found to be friendly and dignified. Back in 1905 this local dignitary had saved the life a British botanist, George Forrest, on the run from Tibetan lamas who had massacred all other westerners in the Mekong valley. At that time the Tibetans greatly resented the presence of western missionaries in the Mekong valley, seeing them as a springboard to convert all of Tibet to Christianity. Their anger cumulated in the murder of the western missionaries in the area around Atuntze [now known as Deqin], and their severed heads being put on display at the monastery there. Ironically the westerners in north west Yunnan were given tacit support by the Chinese authorities, who wanted to destabilise and undermine the political power of the Tibetan lamas.

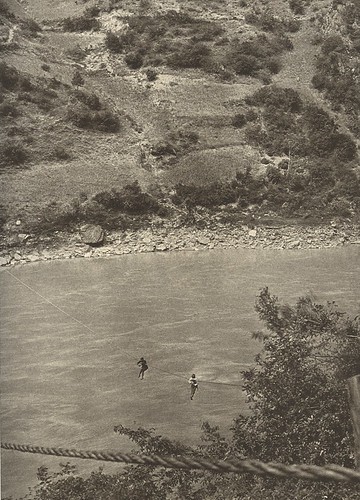

Rock noted that the scenery became grander as they proceeded northwards from Yetche. He was now hemmed in by steep hills on both sides. And it is this narrowness of the valleys that has given the Mekong and Nu canyons their unique mode of transport - the cable crossings of rivers, like the flying fox. In other broader valleys these cable crossings would not be feasible. But Rock describes in great detail how he and the whole of his entourage - 15 men with all their horses and mules and supplies - were conveyed across the roaring river on rope slides.

He was intending to do this at Cizhong, but was persuaded to try a few km further north as the Cizhong rope was past its use by date of three months!

Once across the river, Rock backtracked south to the mission station at Cizhong, where he met the French priest Pere Ouvrard who had been working in this area for 14 years. Again, it is strange that Rock says almost nothing about Cizhong and its distinctive and remarkable Catholic church. Perhaps he wanted to be the centre of the narrative and did not want to draw attention to the fact that others had been here well before him. Or perhaps it had something to do with his aversion to the Catholic church after his unhappy childhood experiences of having the faith rammed down his throat by an overbearing and obsessively religious father.

Rock only mentions that the priest helped him recruit a further 13 Naxi, Lutzu and Tibetans to help on the next stage of his journey - the crossing of the Mekong-Salween divide.

Joseph Rock did not like staying in small towns like Shiku. He loathed the dirtyness and disrepair, and he had little regard for the opium smokers and corrupt and incompetent local officials he had to deal with.

Rope wire crossing: Rock managed to transfer his whole retinue across the Mekong river in this way.

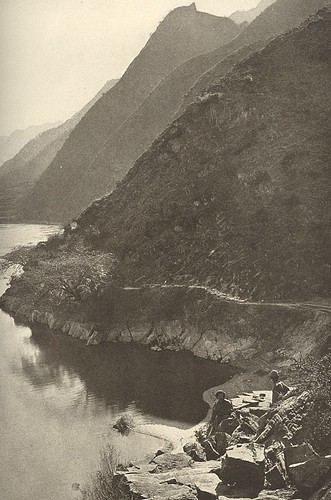

The Mekong river at Cizhong, looking north towards Mt Kawakarpo.

The Mekong looking south from near Cizhong.

A picture taken by Joseph Rock in 1924 of the Yangtze river, near Shigu. He said the narrow trail was almost impassable, and he marvelled at the temple built on top of the conical peak at centre right.

A young Tibetan hunter as seen by Joseph Rock along the banks of the Mekong in 1924.

No comments:

Post a Comment