The three sacred peaks of Konka Risumgongba were traditionally a place of pilgrimage for many Tibetans. But when Rock visited them in 1928, there had been no pilgrims there for more than 20 years, because an assortment of particularly nasty Tibetan bandits ["the scum of the outlaws"]had taken the mountains as their hideout.

"Should any outsider now venture into Konka land he would be robbed then slain, after which the Konka outlaws would resume their own pious pilgrimage!" wrote Joseph Rock.

The situation had come about because of the anarchic state of the Tibetan borderlands at that time, as Tibetan chiefs were usurped by encroaching Chinese warlords. The Konkaling peaks were traditionally in the domain of a Litang Tibetan prince, but he had been overthrown by the Chinese warlord Chao Er Feng in 1904. The Konkaling district was then nominally ruled by a Chinese magistrate, but in practice the magistrates kept well away after several were murdered by Tibetan outlaws.

In this vacuum of authority the outlaws made the Konkaling their stronghold, and were ruled by a headman known as Drashetsongpen - a former lama of the Zhongdian monastery. Drashi and his mobs of cut-throats roamed as far as Kangding and Lijiang to do their plundering, favouring the opium, musk and furs carried by the mule caravans. They attacked in mobs as large of six or seven hundred on horseback, and would raze whole settlements to the ground.

Their loot was sold by Drashi's brother, who acted as a peaceful merchant, plying his business in the main market towns of Kangding and Lijiang and Dali where his brother had recently been robbing!

The Muli king feared the bandits, but he also found them to be a useful deterrent against the encroachment of ethnic Chinese gold hunters into Muli. He did a deal with the Konkaling bandits - he granted them right of way over his roads [to plunder other areas], and paid them off in return for not being molested. This was probably his best defence - as Rock explained, the Muli king did not have much of an army:

The Muli king's domain is like a fenced penitentiary, for none of his subjects is allowed to leave the country, and even Chinese with families who remain a year in the kingdom become automatically subjects and are henceforth forbidden to quit its borders. Peasant is set to watch on peasant, spy and report. Hence their everlasting cringing and crawling in the presence of the [Muli] king and even before his lamas. Such a condition does not foster a fighting spirit.

Instead, for immediate defence the king relied on a few tough Tibetan inhabitants of the village of Garu, which bordered the Konkaling district. These Tibetans, in contrast to those of Muli, were a fearless lot who the Muli king kept in check by occasionally decapitating a few of them or crippling them by having the tendons in their legs severed!

In the spring of 1928, the Muli king sent a letter to Drashi on Rock's behalf, asking to grant him safe passage around the mountains. The king advised Rock to make his trip as brief as possible, and to stay clear of the large Konkaling monastery to the north "[which] houses 400 monks always alert to rob, going out periodically on plundering expeditions, then returning to prayers."

The present day Konkaling monastery [Gongling Si], where once 400 bandit monks lived.

Joseph Rock set off on the 13th of June 1928 with 36 mules, 21 Nashi assistants, a soldier escort and - most usefully - the head lama of Muli monastery to act as guide and king's representative.

"This lama was like a magician in fairy tales. Without him we would have starved. Of course, we paid for everything; yet only through his commands and influence could food be obtained in that lean and hungry country."

They crossed over the 16,000 foot high peaks of Mt Mitzuga, behind Muli, seeing rare birds such as the rose finch and a species of elk known as the wapiti ["which the king protects, forbidding his peasants to kill it under penalty of a severe beating with wooden paddles"]. They passed through larch and oak forests and beds of alpine rhododendron bushes and descended into the barren canyon of the Shouchu [Iron River], where the temperatures exceeded 100 degrees in the shade. This canyon was populated by a strange tribe known as the Iron People, related to the Naxi but speaking a different language.

They crossed the river using a rickety old cantilever bridge, that was so unstable that even the seasoned local muleteers crossed on their hands and knees. They then headed north up the river through Iron People territory until they left the river to head west to the village of Garu - the last frontier before entering bandit country.

It was here that Rock had a showdown with his escort, who were too afraid to continue. The Garu Tibetans he found to be a more courageous breed, with airs of "insolence and haughtiness" quite unlike the subservient subjects of Muli. With their plaited hair, the Garu resembled Apache Indians, said Rock. But even these tough warriors were reluctant to escort Rock into the bandit's territory.

As they sat around the campfire, Rock faced a mutiny from his Muli lama guide, who wanted to go back, saying it was too dangerous. Rock seized the moment:

"I rose as if in contempt of their cowardice, and said: 'Am I to be accompanied by Garu men or women?' and wrote a Chinese note to the Muli king, in which I informed him that the lama and the Garu soldiers were afraid to escort me ... this had the desired effect. Now they agreed they would protect me, even with their own lives!"

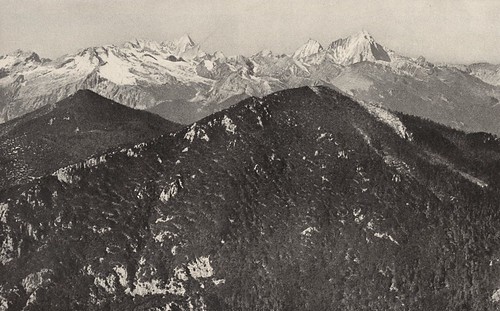

From Garu, Rock and his party made their way up through dense forest to a mountain pass, that marked the beginning of Konkaling territory. From here, he could see the distant peak of Minya Konka, and more immediately, the great mass of mountain known as Chanadorje - Holder of the Thunderbolt - "a truncated pyramid flanked by broad buttresses like the wings of some stupendous bat".

[To be continued]

Chanadorje [right] and the other Konkaling peaks, as Rock first saw them when from west of Mt Mitzuga.

This is a stitched together panorama shot of the Konkaling peaks [very faint on the righ hand side in cloud], also taken from just west of Mt Mitzuga, on our abortive 1996 hike to Konkaling from Muli. As you can see, we had a bit of snow, which eventually put paid to any hopes of crossing the next high pass above Garu.

No comments:

Post a Comment